In the wake of the avalanche of revelations about the scope of domestic surveillance, several people have asked me to help them understand what is going on. So I put together this handy cheat sheet that hopefully explains the key issues.

This is a shorthand version of an explainer I presented last week at the Privacy Law Scholars Conference in Berkeley. With apologies to Donald Rumsfeld, I’ve broken it down into “Known Knowns” and “Known Unknowns.”

Patriot Act Surveillance

Known Knowns:

Who: Verizon, AT&T, and SprintNextel, according to reporting by Glenn Greenwald at The Guardian and the The Wall Street Journal.

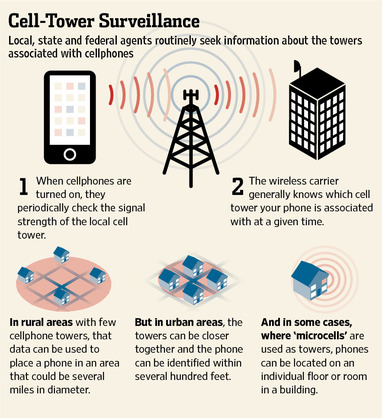

What: Records of every single domestic and international telephone call, including the location from which the call was placed, the serial number of the phone, the number dialed and the duration of the call, according to the court order obtained by the Guardian.

Where: Turned over to the National Security Agency daily, according to the court order obtained by the Guardian.

When: Ongoing for the past seven years, according to Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA)

Why: To “make connections related to terrorist activities over time,” according to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

How: Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court authorizes record collections with a court order every three months, according to Sen. Feinstein. Analysts are required to have “reasonable suspicion, based on specific facts, that the particular basis for the query is associated with a foreign terrorist organization” before querying the database of call records, according to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Legal authority: Section 215 of the Patriot Act allows the FBI to order any person or entity to turn over “any tangible things” for “for an investigation to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities, provided that such investigation of a United States person is not conducted solely upon the basis of activities protected by the first amendment to the Constitution.”

Known Unknowns:

Is it legal? Senators including Ron Wyden and Mark Udall have accused the government of secretly reinterpreting the law.

What happens to innocent people’s data? It’s not clear.

Are some telecom companies refusing to participate? It’s not clear.

Does it prevent terrorism? Officials have pointed to two terrorist attacks that were flagged by this program: a New York city subway bombing plot that was foiled, and the Mumbai terror attacks, which were successful.

Have intelligence officials lied about the existence of the program? Maybe. Sen. Wyden has asked Director of National Intelligence James Clapper to explain his previous denials to Congress. Last year, National Security Agency Director Keith Alexander told Congress “we don’t have technical insights in the United States.”

PRISM Surveillance:

Known Knowns:

Who: Microsoft, Google, Yahoo, Facebook, YouTube, Skype, AOL, Apple, PalTalk, according to slides obtained by The Guardian and The Washington Post.

What: Content of Internet communications including e-mail, chats, instant messages, according to the slides.

Where: The government can only use this capability to target persons “reasonably believed to be outside the United States” even though the electronic communications may travel through United States computer services, under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 2008.

When: Since 2007, tech companies have worked to build systems that let the government collect this data, according to the slides.

Why: The government says it needs this capability to investigate terrorism, hostile cyber activities and nuclear proliferation.

How: The government must obtain a search warrant from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.

Legal Authority: Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 2008 authorizes the “targeting of persons reasonably believed to be located outside the United States to acquire foreign intelligence information.”

Known Unknowns:

Is this blanket surveillance? It’s not clear. Before the 2008 law was passed, the government had to identify the target of surveillance. The 2008 law allowed the government to issue “programmatic warrants” that are not based on the identity of an individual, but rather on broader criteria.

How is the data technically handed over? We don’t yet know all the technical details of how data is turned over to government. Companies have said they don’t provide “direct access” but that doesn’t preclude other ways of sharing bulk data. Google told Wired on Tuesday that it either provides information by hand or secure FTP.

What happens to innocent people’s data? The law requires the government to minimize the use of data about U.S. persons.

In Summary: The Patriot Act surveillance program is potentially illegal, officials may have lied about it to Congress and it collects information about nearly every single person in the United States. The Prism program is legal, is likely less broad and has some safeguards to protect innocent U.S. residents.

There’s a reason that former Department of Justice attorney Mark Eckenwiler, who specialized in electronic surveillance law, has suggested calling the Patriot Act surveillance program “Hoover.”