It wasn’t easy to unfriend all 666 of my friends on Facebook. Here’s my Marketplace radio segment about how I had to pay a friend to push the unfriend button for me.

U.S. Terrorism Agency to Tap a Vast Database of Citizens

By JULIA ANGWIN

Top U.S. intelligence officials gathered in the White House Situation Room in March to debate a controversial proposal. Counterterrorism officials wanted to create a government dragnet, sweeping up millions of records about U.S. citizens—even people suspected of no crime.

Counterterrorism officials wanted to create a government dragnet, sweeping up millions of records about U.S. citizens-even people suspected of no crime.

Not everyone was on board. “This is a sea change in the way that the government interacts with the general public,” Mary Ellen Callahan, chief privacy officer of the Department of Homeland Security, argued in the meeting, according to people familiar with the discussions.

A week later, the attorney general signed the changes into effect.

Through Freedom of Information Act requests and interviews with officials at numerous agencies, The Wall Street Journal has reconstructed the clash over the counterterrorism program within the administration of President Barack Obama. The debate was a confrontation between some who viewed it as a matter of efficiency—how long to keep data, for instance, or where it should be stored—and others who saw it as granting authority for unprecedented government surveillance of U.S. citizens.

Read more at The Wall Street Journal and see the full privacy series.

New Tracking Frontier: Your License Plates

For more than two years, the police in San Leandro, Calif., photographed Mike Katz-Lacabe’s Toyota Tercel almost weekly. They have shots of it cruising along Estudillo Avenue near the library, parked at his friend’s house and near a coffee shop he likes. In one case, they snapped a photo of him and his two daughters getting out of a car in his driveway.

Mr. Katz-Lacabe isn’t charged with, or suspected of, any crime. Local police are tracking his vehicle automatically, using cameras mounted on a patrol car that record every nearby vehicle—license plate, time and location.

“Why are they keeping all this data?” says Mr. Katz-Lacabe, who obtained the photos of his car through a public-records request. “I’ve done nothing wrong.”

Until recently it was far too expensive for police to track the locations of innocent people such as Mr. Katz-Lacabe. But as surveillance technologies decline in cost and grow in sophistication, police are rapidly adopting them. Private companies are joining, too. At least two start-up companies, both founded by “repo men”—specialists in repossessing cars or property from deadbeats—are currently deploying camera-equipped cars nationwide to photograph people’s license plates, hoping to profit from the data they collect.

The rise of license-plate tracking is a case study in how storing and studying people’s everyday activities, even the seemingly mundane, has become the default rather than the exception. Cellphone-location data, online searches, credit-card purchases, social-network comments and more are gathered, mixed-and-matched, and stored in vast databases.

Read more at The Wall Street Journal and see the full What The Know series online.

How Grabby Are Your Facebook Apps?

The Wall Street Journal analyzed 100 of the most used applications that connect to Facebook’s social-networking platform to see what data they sought from people. The Journal also tested its own Facebook app, WSJ Social. See the apps tested by the Journal, along with the permissions they ask users to grant them.

Read more at The Wall Street Journal and see the full What The Know series online.

The Surveillance Catalog

The Surveillance Catalog allows readers to peruse secret marketing materials published by companies that make tracking equipment.

Documents obtained by The Wall Street Journal open a rare window into a new global market for the off-the-shelf surveillance technology that has arisen in the decade since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

The techniques described in the trove of 200-plus marketing documents include hacking tools that enable governments to break into people’s computers and cellphones, and “massive intercept” gear that can gather all Internet communications in a country.

Read more at The Wall Street Journal and see the full What They Know series online.

Stewart Baker: Why Privacy Will Become a Luxury

Stewart Baker, the former assistant secretary for Homeland Security, talks with Julia Angwin about the need for balancing privacy rights with security concerns. In The Big Interview, Mr. Baker explains why privacy may one day be a luxury available only to the privileged and the rich.

Your Digital Fingerprint

Companies are developing digital fingerprint technology to identify how we use our computers, mobile devices and TV set-top boxes. WSJ’s Simon Constable talks to Julia Angwin about the next generation of tracking tools.

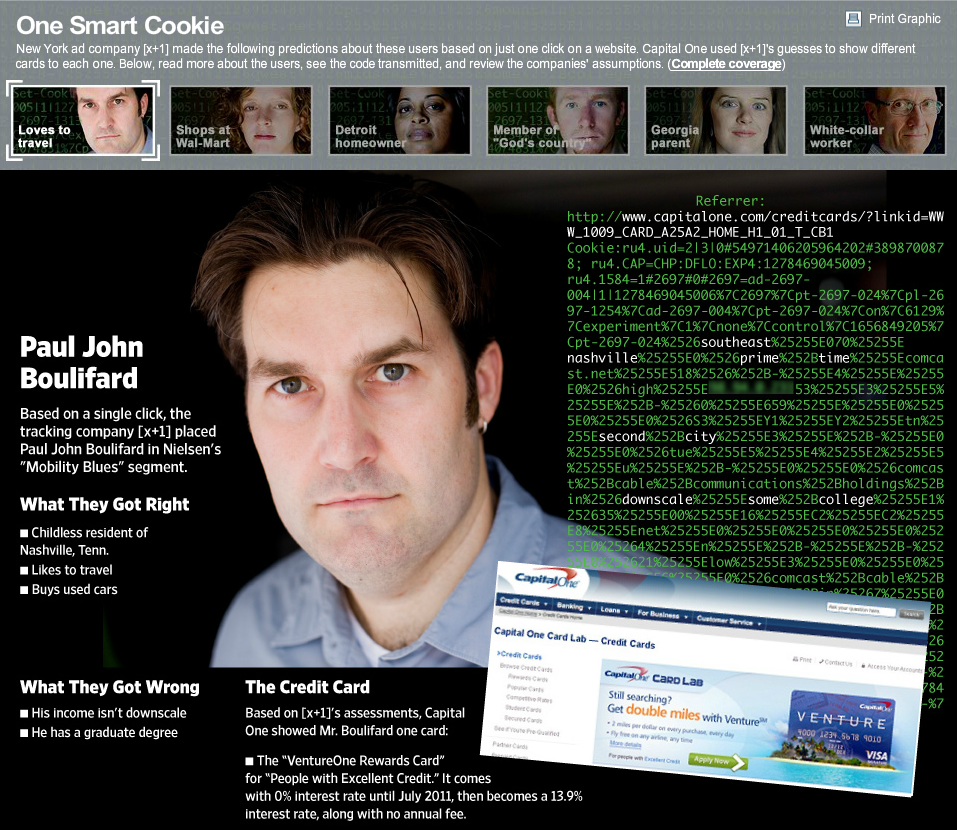

One Smart Cookie

New York ad company [x+1] made predictions about users based on just one click on a website. This interactive shows the company’s assumptions about users and how they affected what credit cards were shown.

Read more at The Wall Street Journal and see the full What They Know series online.

Sites Feed Personal Details to New Tracking Industry

The Wall Street Journal, Page A1

The largest U.S. websites are installing new and intrusive consumer-tracking technologies on the computers of people visiting their sites—in some cases, more than 100 tracking tools at a time—a Wall Street Journal investigation has found.

The tracking files represent the leading edge of a lightly regulated, emerging industry of data-gatherers who are in effect establishing a new business model for the Internet: one based on intensive surveillance of people to sell data about, and predictions of, their interests and activities, in real time.

Read more at The Wall Street Journal. See the interactive database accompanying the article and see the full What They Know series online.